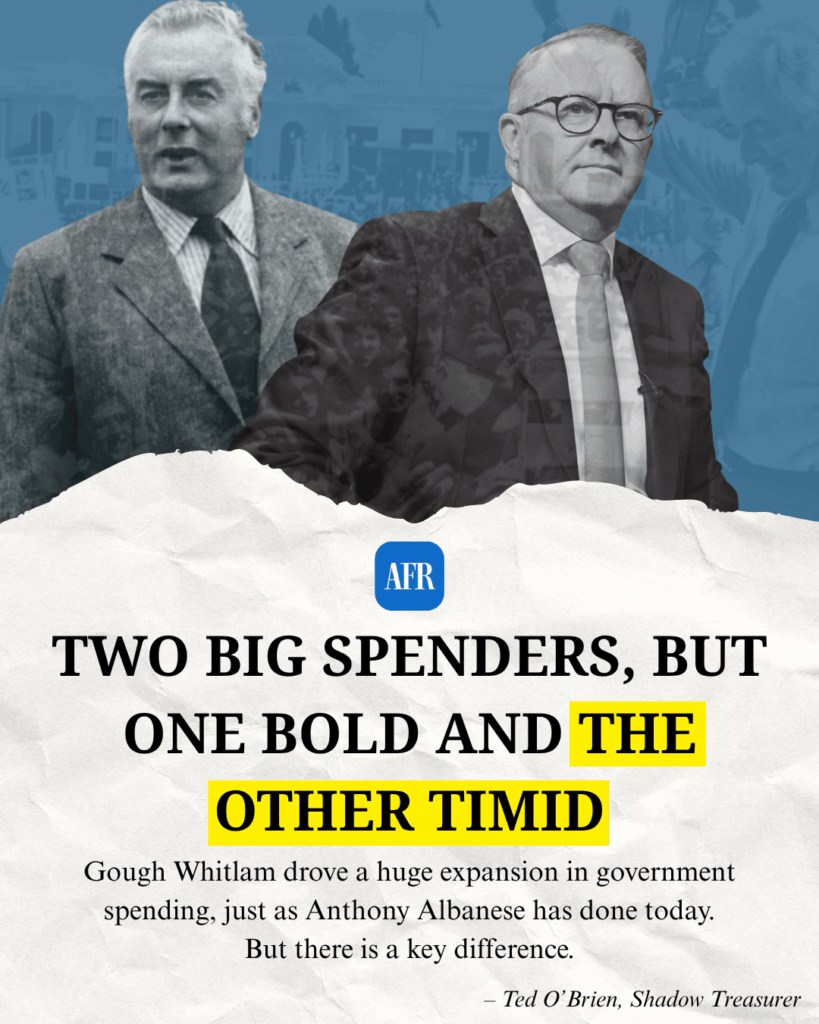

Gough Whitlam drove a huge expansion in government spending, just as Anthony Albanese has done today. But there is a key difference.

As published in the Australian Financial Review 10 November 2025

The recent surge in both inflation and unemployment has many of us thinking back to the bad old days of the 1970s.

My colleague, opposition finance spokesman James Paterson, was apt to warn recently of the spectre of stagflation, which so harmed our prosperity through the 1970s.

For this to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Gough Whitlam’s dismissal is uncanny.

Back then, inflation was sparked by the 1973 oil crisis – and then fuelled by a massive surge in government spending under the new Whitlam government.

Today, inflation was sparked by a pandemic and constraints on energy supply – and then fuelled by a massive surge in government spending under the new Albanese government.

Back then, it was called “stagflation”. Today, many are calling it “Jimflation”. Regardless, the driver is the same: massive expansion of government.

When Treasurer Jim Chalmers boasts that his first two budgets were in surplus, someone ought to remind him that the first two budgets of Whitlam’s then-treasurer, Frank Crean, were also in surplus. But the third budget plunged deep into deficit – just as Chalmers’ did – as the spending promises finally outran the revenue upgrades.

As with today, Labor’s profligacy was initially satiated by rivers of gold flowing into the Treasury, principally due to inflation-driven bracket creep boosting income tax revenues.

Hawke and Keating learnt the hard lessons from that period, fundamentally changing the Labor Party with an injection of rational economics and fiscal discipline.

But such economic prudence is gone now. A big-government revolution is once more upon us.

In the past three years, economic activity has risen by $300 billion per year while government spending has risen by $150 billion per year. That is, the Commonwealth has accounted for half of all new economic activity created – twice its usual role.

Over the past two years, 80 per cent of new employment has been in the non-market sector despite its accounting for just 30 per cent of employment.

Right now, government spending is growing at four times the rate of the economy and has reached its highest level outside of recession since 1986.

That’s the level that prompted Hawke and Keating to slash spending and shrink government. Albanese and Chalmers are no Hawke and Keating, that’s for sure.

Chalmers is keen to claim the private sector is “taking over” from the public sector as the primary driver of growth. But a breakdown of the national accounts tells a different story.

Separating demand into consumption and investment shows the recent slowdown in public demand has been driven entirely by a fall in public investment, which is lumpy as big projects stop and start.

Looking just at consumption, which is a better indicator of the true posture of government, public consumption in fact continues to grow more strongly than household consumption. Meanwhile, business investment is at a standstill.

This proves Chalmers’ claim that the private sector is taking over to be false.

Just as in the 1970s, the consequences of Labor’s big-government experiment are a disaster.

Since the Albanese government was elected, productivity hasn’t just been sluggish – it’s gone backwards, by 5 per cent. Chalmers boasts that real wages are growing again. But what he doesn’t say is that it will take a decade to recover the real wage falls so far on his watch.

Inflation is due to stay above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s target band until 2027, and the RBA’s forecasts suggest it cannot offer any additional interest-rate relief from here if it is to achieve its target. Many economists are now saying the next rate move will be up.

Chalmers boasts that Labor has created 1.2 million new jobs. But what he doesn’t say is that there are also 1.8 million more people. So his 1.2-million figure tells the story of additional people who have jobs, not additional jobs for existing people.

In fact, the existing people have fewer jobs – that’s why the unemployment rate has hit its highest level since the pandemic. When the Coalition left office, the unemployment rate had a three in front of it; under Labor, it has a four in front of it.

These are not the economic conditions for sustained prosperity.

That’s what happens when government expands to account for half of all new economic activity when the economy is already beyond capacity. Everything else is squeezed out.

Albanese’s economy is a basket case. Just as Whitlam’s was. Nevertheless, despite the many similarities, there is one big difference between Albanese and Whitlam.

For all his faults, Whitlam left a lasting legacy. He gave us universal healthcare, later called Medicare, a source of pride for all Australians that now has broad and enduring bipartisan support.

To the contrary, Albanese has no legacy whatsoever. And, three years in, having now been in power longer than Whitlam, he doesn’t even have an economic agenda to speak of, upon which a future legacy might be built.

Whitlam was a reckless big spender, but he was at least bold and visionary.

Albanese is also a reckless big spender, but he is timid and unimaginative. But perhaps we should be grateful Albanese is no Whitlam. Who knows how much more damage he’d do if he started getting big ideas and the courage to pursue them?