As published in The Australian, 11/1/23

On my first visit to Japan as an impressionable 14 year old, my mother gifted me a book on Akashi Nagai, a physician who survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

Despite losing his wife and damaging his limbs, Dr Nagai compared victims of the bomb to “a sacred offering to obtain peace”.

Visiting Nagasaki’s bomb site seared an indelible memory in my teenage mind and also an unspoken aversion to all things nuclear.

Some three decades after my first visit, I was back.

This time, understanding nuclear was foremost on my mind.

What had changed since my initial trip?

I had come to realise nuclear’s capacity for good.

This awakening came slowly – reading the odd newspaper article and working in countries powered by nuclear energy – but it accelerated when I chaired a parliamentary inquiry into nuclear energy in the last term of government.

I learnt how nuclear technology improves lives in manifold ways – from diagnosing and treating cancers to improving ecosystems; from desalinating water and reducing contaminants in food to various industry applications.

What intrigued me most, however, was nuclear technology as a source of industrial-scale, zero-emissions energy.

In a decarbonising global economy, this is extraordinary.

But, there remain mixed views on nuclear energy in Australia.

That’s why I launched a national survey last month to gauge perspectives on the benefits, risks and unanswered questions about nuclear energy. On the question of risks, what Australians told me was that nuclear proliferation and nuclear accidents were key issues.

Where better to learn about such risks than Japan? This is a country that’s suffered two atomic bombings in World War II and a major nuclear accident in 2011.

I decided to fly Japan to understand these issues first-hand.

And what I found were a Japanese people who are philosophical about their nuclear past and pragmatic about their nuclear future.

In Tokyo, prominent scientist Moto Yasu Kinoshita said – despite the barbarities of the war – Japan’s nuclear engineers possessed a “special intention” to develop the technology for “peaceful use and human happiness”.

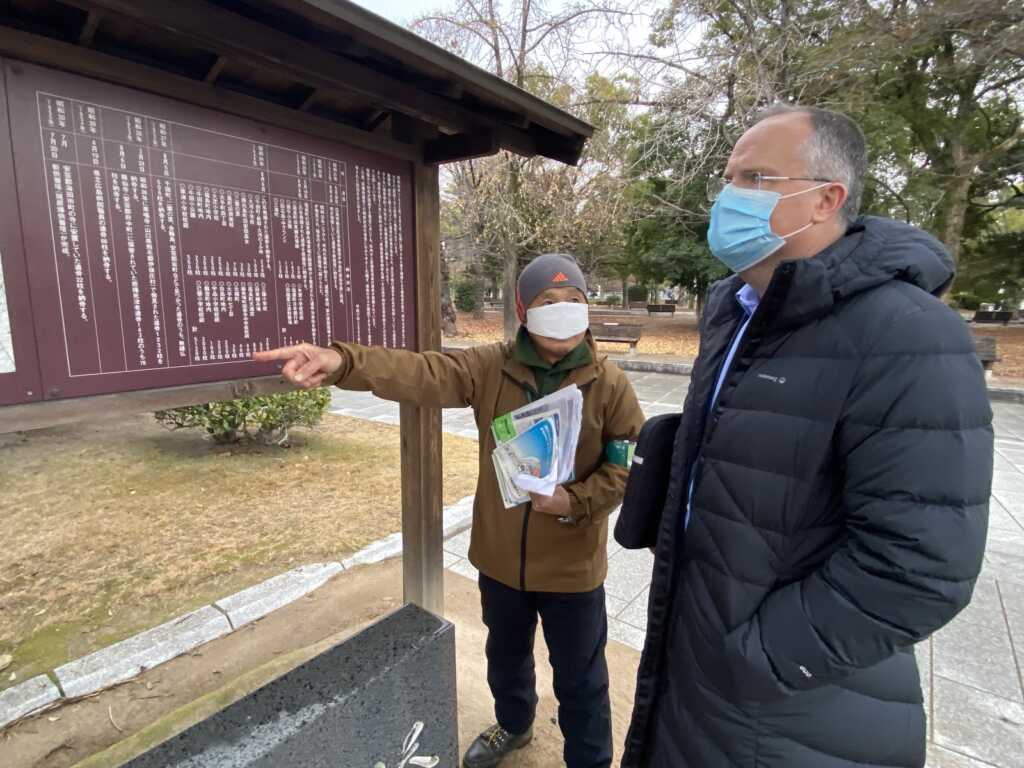

In Hiroshima, my tour guide at the Peace Memorial Park, Yukio-san, told me plainly that despite the atrocity of the atomic bomb, Japan turned to nuclear energy because “we need cheap energy”.

To fuel a manufacturing sector that accounts for 20 per cent of a $7.2 trillion economy, cheap energy is essential. And nuclear energy is cheap energy.

According to a 2021 report by Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, nuclear energy is cheaper than wind and solar, and on par with coal, hydro and liquefied natural gas.

Japan should know: it uses all these technologies, and knows their cost at a sophisticated level, based on a whole-of-system methodology that accounts for variables including capacity and asset lifespans. It’s the price paid by households and businesses that count and this methodology most accurately tells that story.

Economics isn’t everything, however. Energy security also looms large in Japan. Like Australia, Japan is surrounded by oceans on all sides and it has no international interconnections from which to draw electricity.

But, unlike Australia, Japan isn’t blessed with abundant natural resources; it imports 90 per cent of its energy needs. Japan can’t afford to be exposed on energy supply, especially amid volatility in Ukraine, escalating regional tensions, and its proximity to nuclear-weapons nations like China, Russia and North Korea.

Its plan includes increasing supply chain autonomy and diversifying its energy sources.

Where oil and gas supplies fall victim to geopolitical instability, nuclear becomes increasingly important as a stable power source at low operational cost.

And with a capacity factor higher than other energy sources, nuclear power plants can be relied upon to produce maximum power.

Japan’s emerging capabilities in the nuclear fuel cycle mean it could produce energy for years relying solely on its domestic fuel stockpile; the energy source which is nearly 8000 times more efficient than other fossil fuels.

Japan has also joined global efforts to tackle climate change.

Like Australia, it is aiming to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. But, unlike Australia, Japan is putting all technologies on the table to get there. Referencing an International Atomic Energy Agency scenario where renewables account for two thirds of energy supply, Japan’s Strategic Energy Plan aims to maximise renewables while recognising the need to “improve the flexibility of the electric power systems … in response to the increase in variable renewable energy sources”.

Japan’s plan doesn’t position nuclear energy as competing with wind and solar, but rather complementing them. It therefore came as no surprise when, during my visit, Japan’s nuclear regulator endorsed a plan to extend the life of existing nuclear power plants and invest in next-generation reactors to achieve 22 per cent of nuclear in Japan’s energy mix by 2030.

It would be fair to ask why Japan is expanding its fleet after experiencing the world’s biggest nuclear accident since Chernobyl.

It was March 2011 when the largest earthquake in Japan’s recorded history struck, triggering a tsunami with waves over 13m that smashed into the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and flooded the site, including emergency diesel generators.

As nuclear meltdowns and hydrogen explosions ensued, more than 80,000 people were evacuated from the region to avoid radioactive contamination.

The tsunami tragically killed about 20,000 people, mostly from drowning. But the nuclear accident, grave as it was, caused no death to workers at the plant nor any radiation casualties.

A 2013 United Nations report concluded: “No radiation-related deaths or acute diseases have been observed among the workers and general public exposed to radiation from the accident.

“The doses to the general public, both those incurred during the first year and estimated for their lifetimes, are generally low or very low.”

Nevertheless, Fukushima continues to be portrayed by some as an uninhabitable nuclear wasteland. I added it to my itinerary to find out for myself.

Fukushima is still hurting after a triple whammy of an earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear accident.

Within the exclusion zone, debris remains littered alongside gutted homes. Upon spotting a child’s bicycle outside an empty shell of a home, I wondered about the fate of its owner; a little girl or boy, maybe the same age as my own children, who may have been swept away by an avalanche of uninvited water.

But, outside the much-reduced exclusion zone, things are looking up. One of my guides, with a long connection to the area, is among countless multi-generational families rebuilding their community.

Primary producers are in full swing: local fish, fruit and vegetables not only tasted great, but were perfectly safe and of top quality.

Fourth-generation returnee, broccoli farmer Yoshida-san, is selling this year’s harvest right across Japan, and plans to double his operation from 50ha to 100ha over the next two years. Yoshida-san was pragmatic in his view of the nuclear accident: his chief frustration was the region’s extensive evacuation including his farming areas and factory.

Japan responded to the Fukushima accident by either closing or upgrading existing plants and temporarily pausing plans to build additional reactors.

Given the notoriety of incidents like Fukushima, people typically expect the worst when it comes to nuclear energy. Yet, the evidence says that nuclear is the world’s safest form of energy: compared to coal, oil, biofuel, gas, hydro, wind and solar, deaths attributed to nuclear energy rank lowest on the mortality scale.

Even so, public perception isn’t easy to move. It’s one of the reasons a social licence – that is, public acceptance – is so important.

In Japan, it’s paramount.

This was evident when I visited Japan Nuclear Fuel Limited in Rokkasho, in the snowy northern Aomori prefecture. JNFL is a giant within Japan’s nuclear industry; operating a uranium enrichment plant, managing the waste from all Japan’s nuclear power plants and developing reprocessing capabilities to recycle spent fuel.

“More than anything else, we are able to operate thanks to the trust that the people of the community have placed in us,” said JNFL president Naohiro Masuda.

With 64 per cent of its 3000-odd employees hailing from Aomori prefecture, and many others working for 1200 companies that contract to it, the community and JNFL are intertwined. JNFL also relies on a social licence internationally, especially due to its ability to separate plutonium from uranium; plutonium being integral for nuclear weapons.

As nuclear physicists know, the capacity to generate nuclear energy doesn’t easily translate into the capacity to develop nuclear weapons. Only eight of 33 nuclear-energy nations are thought to possess nuclear weapons capabilities.

Like Moto-san in Tokyo, Yoiki-san in Hiroshima, ministry officers and everyday people with whom I spoke, JNFL representatives displayed a reverence for the safe and peaceful use of nuclear power.

After parting ways with JNFL, my mind returned to Dr Nagai.

“We should utilise the principle of the atomic bomb. Go forward in the research of atomic energy contributing to the progress of civilisation,” he wrote.

Ted O’Brien is the Coalition’s energy spokesman.

Click HERE to download the article.